History of Branford House

Excerpted from The History of Branford House and Morton Plant by Karen Bakowski

Branford House was originally a 31-room mansion that rivaled those found in Newport. It was built at a cost of $3 million in 1903 when Groton Savings Bank at the time had $312,738.39. Features included panoramic views of Fishers Island and Long Island Sound, a two-story fireplace, a winding staircase of imported Italian marble, and paneled walls carved by Italian and German craftsmen.

Morton Freeman Plant was a wealthy businessman who did not come into his own until the middle of his life. Born to Henry Bradley Plant, a very wealthy railroad and steamship magnate, and Mrs. Ellen Blackstone, Morton grew up a playboy with yachting as one of his famous pastimes. He was on one of his yachting trips when his father died in 1899. Even though Morton was president of his father’s Southern Express Company, Henry did not want Morton, then 47, to run all of his businesses. He tried to ensure this by skipping the inheritance by two generations and willing his estate to his youngest and yet unborn great-grandchild when he reached the age of 21. Rather than settle for the yearly stipend of $30,000 each, Morton and Henry’s then-second wife contested the will and won. Morton now inherited two-thirds of his father’s $22 million fortune, and with this windfall, Morton Plant spent lavishly.

Although he spent like a playboy, Plant grew in success as a businessman. From his father’s fortune of $22 million, it was reported that Morton had amassed around $50 million by the time of his death. He became the director of numerous railroad, shipping, and banking communities, including the National Bank of Commerce in New London.

Even though he only summered in Groton, Plant loved the region and soon became a benefactor of Groton and the surrounding areas. He supported and owned a minor league team in New London, The Planters. It has been reported that Plant endowed $1 million to what is now Connecticut College, and became the primary benefactor because he wanted to hurry the board meeting along so he could see his team play. Through the development of his estate, hotels, and farms, Plant created many of the roads in the Poquonnock area as well having established a trolley line, the Shoreline Electric Railroad (that ran through southeastern Connecticut into Rhode Island). He is remembered fondly in Groton for buying the town a $25 thousand town hall and, at a later date, erasing a debt of equal value. It had been reported that he once drove by a church badly in need of paint. He gave the lady of the house his card and told the reverend to have the church painted and to send the bill to him.

It is thought that Plant chose to build his summer “cottage” at Avery Point for a number of possible reasons. Plant did not have an interest in being part of the social circles of Newport. He chose instead to be in the remote, yet increasingly popular, Groton area. He wished to be a gentleman farmer and had a great interest in agriculture. The undeveloped Groton area allowed him to build his greenhouses and farms in a way that he never could do in the already-developed Newport. With his love of the ocean, Avery Point’s panoramic views of Long Island Sound surely may have drawn him here.

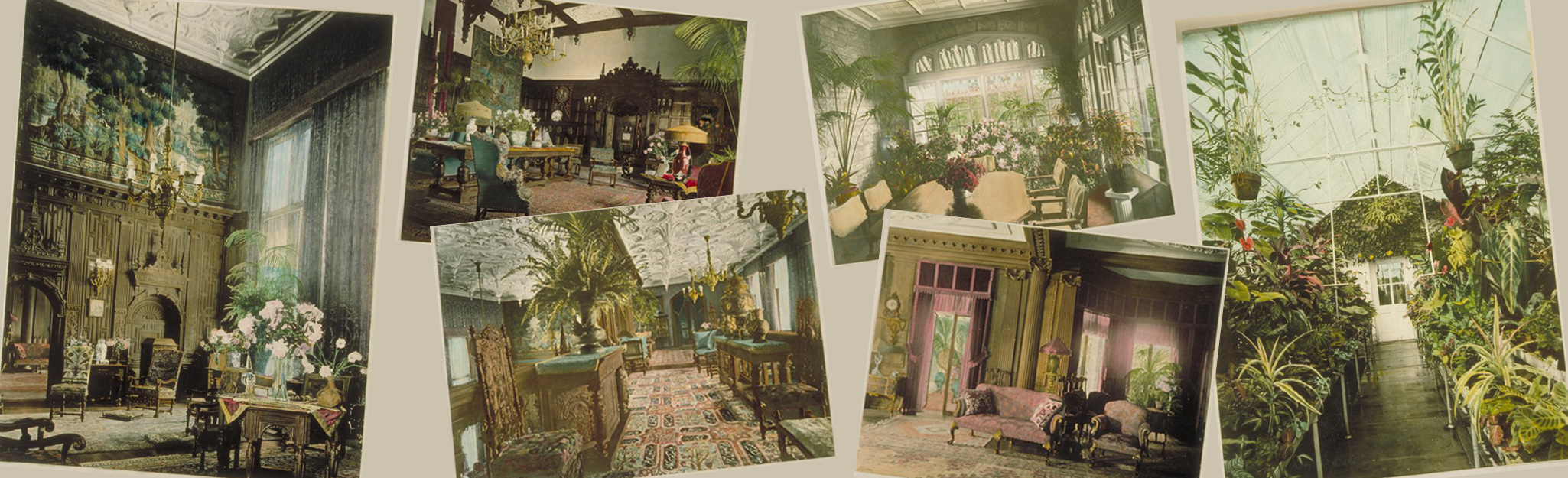

Named after the town where he was born, the Branford House was designed by his wife Nellie, who had studied architecture at the Sorbonne in Paris. English architect Robert W. Gibson carried out her plans. The exterior was done almost entirely in the Tudor style using granite quarried from the grounds in order to harmonize with the estate’s natural surroundings. The interior, on the other hand, was a melange of several different styles that Mrs. Plant wished to dabble in including Gothic, Baroque, Renaissance, Classical, and even Flemish. Materials used for the interior ranged from rich woods such as mahogany, oak, and walnut, to imported stone and metals such as onyx, marble sandstone, bronze, and iron. Plant required the services of hundreds of European carvers to do the incredible ornamentation of fireplaces, pillars, and panels, each one being entirely different from the next. In some cases, the use of imported materials was not enough for the rich tastes of the Plants. In one case, an entire room was imported. It was dismantled from Cornwall, England, reassembled in the mansion, and became the Plant’s music room. Please see images from the Connecticut Digital Archive (CTDA).

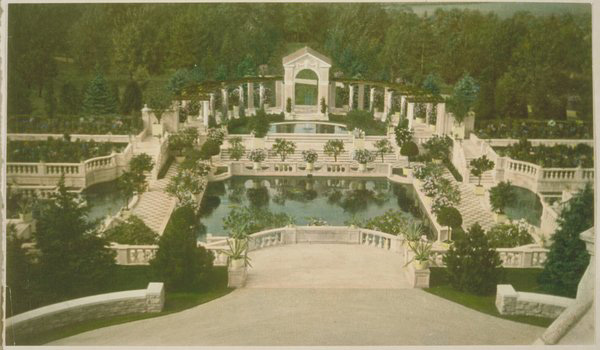

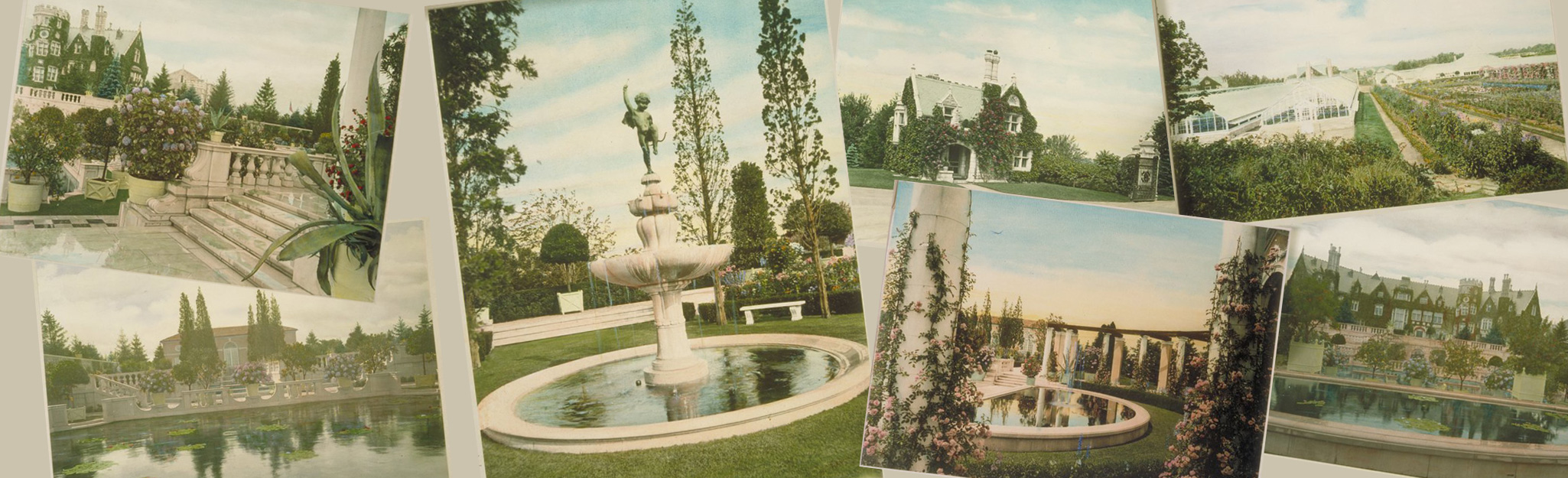

There were also many unique features that set the Branford House apart from its contemporaries. A two-story fireplace was the focal point of the house. Plant also put in an elevator to reach the many floors of his home. In the basement, Plant had a system to take hundreds of items of clothes on a conveyer around the fireplace until they dried. There are doors that lead to the outer wall and one can only guess their use. With his interest in horticulture, Plant made sure that his garden would exceed all others. Once again, Plant used the craftsmen from Italy to create literally tons of marble and granite carvings for the gardens on his estate. They created vast arrays of arches, grand staircases, checked marble paving reflecting pools, fountains, statues, pediments, and pink marble columns in what would be called an Italian revival garden style. He had a fondness for tropical plants and had Italian topsoil shipped to cover his land to ensure their well-being. To ensure that these plants would live through the harsh New England winters, all of these tropical plants would be dug up and housed in large conservatories. One such greenhouse stretched the length of the Branford House to Shennecossett Road. These also housed Plant’s flowers and plants that often won awards at New York flower shows.

Plant also used his money to improve the aesthetic quality of his estate in a rather unusual manner. He could smell the odor of rotten fish from his back door caused by the Quinnipiac Fertilizer Company, which was situated on nearby Pine Island. He solved this problem by buying the island and shutting down operations there. It became a playground of sorts in later years for his granddaughters, who loved to play in the over 500-tree orchard that was planted there.

Plant also developed beyond the Avery Point estate onto the Poquonnock Plains area with a model farm that was over 300 acres. He had a 22,250-foot cow barn, an area to raise prize poultry and other small livestock, and fields to grow various vegetables and fruits. He hired a staff of experts to keep everything running. When all was finished, Plant’s 70-plus-acre estate included the mansion, a boathouse, extensive greenhouses, gatehouse, stables, boarding house, tenant’s houses, superintendent’s house, plumbing shop, carpenter’s shop, storehouse, wharf, beach, lavish gardens, pond, and orchard. Even though the Plants only used the mansion for 30-60 days a year, there was a staff of 50 working year-round to keep up the estate. After his death in 1918, the estate was passed on to his son Henry, then to Plant’s daughter-in-law. It was reported that Branford House was eventually sold for $55,000 at auction in 1939. The furniture was then sold off and the mansion left. It soon came into the hands of the State of Connecticut.

From a quitclaim deed, it became the property of the United States Coast Guard in 1941. The mansion was used for administrative offices and family quarters for the commanding and executive officers. The west wing, which was the music room that was imported from Cornwall, was used as the station chapel until it was almost completely destroyed by fire in 1963. The grounds were transformed as well. Because of wartime concerns, the lush gardens were bulldozed into the sea to make room for barracks. Much of the marble is still on the rocky coast of the point. Pine Island was used for dynamite practice.

A stipulation of the quitclaim deed was that an aid to navigation must be built within five years or the land would revert back to the state. It was also cited that a lighthouse was to be built as a memorial to coast guardsmen and/or lighthouse keepers. The lighthouse was completed in March of 1942, which made it the last lighthouse built in Connecticut. During the war, it remained unlit, but once hostilities ceased it was lit and stayed so until June 25, 1967.

It was at this time that the Coast Guard training center relocated and the land reverted back to the state. The Coast Guard still maintains a small research crew and has used the lighthouse for various navigational experiments. Shortly after the Coast Guard training center relocation, the estate was turned over to the University of Connecticut as a branch campus.

Avery Point and the Branford House have had a unique history over the past century. The mansion has gone through many transformations – from being the home of one of the area's most colorful and beloved benefactors to a military establishment, and finally becoming an institution of higher education. The refurbishment of the mansion was finished during the summer of 2001.